Apples are an American icon. And while it rarely generates financial headlines, the apple industry is booming in our country.

This fruit has had a special place in our national heart since the days of Benjamin Franklin, if not before. Think about all of the sayings about apples that have withstood the test of time:

“An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

“You are the apple of my eye.”

“American as apple pie.”

I could go on, but these universally known expressions go to show apples are a thriving part of our culinary heritage. They are also a healthy part of our national economy.

I have always loved apples. I grew to love the fruit while working in an orchard as a kid and plan to buy an orchard in retirement. Being surrounded by apples has led me on the quest to find the perfect apple variety. My kids and I rate apples…1-10. This started over the last few years as grocery stores have gotten more adventurous with their selection and moved away from the traditional red un-delicious.

Every once in a while, we find a new favorite batch. Here’s my current rating:

- Crisps Pink/Pink Lady

- Koru

- Honey Crisp

- Jazz

- Gala

Put this all together with a new fascinating economic story and we get to the subject at hand. Apples. Real Apples, as in the fruit…

It’s a story about how certain types of apples have become brands powerful enough to fuel a $7 billion American industry.

Today, there are so many apple varieties in the produce section – Gala, Red Delicious, Fuji, Granny Smith, Honeycrisp, Golden Delicious, McIntosh, the list goes on. Turns out, it wasn’t always this way.

Back in the 1980s, there was just the “stoplight selection” of apples: red, yellow or green. Sales were low and growers were going broke. The most common apple, Red Delicious, had become just a commodity, leaving growers floundering because their pricing power had dwindled to nearly non-existent.

Enter Denis Cortier, an apple grower and the owner of Peppin Heights Orchards in Lake City, Minnesota, and David Bedford, an apple breeder, or inventor, if you will. Arguably, these two like-minded guys singlehandedly reversed the downward trend in apple consumption.

It all started when Bedford ate a fresh yellow apple from an orchard in Michigan. His college buddy had brought him a bushel. Bedford was knowledgeable about the apple industry and was well aware that it was on the rocks. The reason for the decline, Bedford posited, was that the apples that growers were currently producing lacked flavor, crispness, and that “je ne sais quoi.”

For Bedford, it was love at first bite. That apple was all the inspiration Bedford needed to roll up his sleeves and get to work. From that point forward, he devoted his work to finding and creating better apples.

Bedford was an agricultural inventor in this regard; he mixed and matched different types of apples and crossbred them. Patience was his virtue (remember that apple trees take five years to produce fruit). But so was innovation.

This creative horticulturalist planted a vast trial orchard at the University of Minnesota, with 5,000 to 6,000 separate new hybrid apple trees. Bedford knew that even with that many plants, he might not produce a new apple good enough to get introduced into the market. But he went through trial and error, taste-testing hundreds of apples, day after day.

Then one day, which Bedford still remembers, he tested an apple from Tree Number 1711. When he first tasted the fruit, he was confused but also intrigued. Its flavor hinted at the very best of a sweet summer watermelon, and its flesh was crisp, almost like ice chunks sliding off a glacier.

He named it the Honeycrisp.

Bedford was a modern-day Johnny Appleseed, but his story is much bigger than one of a simple discovery. Like every story of innovation that has sparked seismic change, this discovery wasn’t an accident. Bedford’s work was a tremendous undertaking, and it has had equally massive impact on the American economy.

Today, Honeycrisp is a household name.

There more to the story. Remember that we mentioned a second pioneer, Denis Cortier. He was as instrumental to bringing Honeycrisps to market as Bedford was at bringing them to life.

Here’s the deal – no one wanted to buy these new apples. Plain and simple, stores weren’t ready for them in those days; they were stuck in the old (albeit obsolete) tradition of red, yellow and green. (Remember, if you will, the days before kale and organic fennel and microgreens in almost every grocery store.)

So, Bedford had found the perfect apple, but he couldn’t sell it. Until he met Denis Cortier, an apple grower from Minnesota who had also been on a quest to find the perfect apple.

Cortier bet big on Honeycrisps and got to planting. And it paid off, big time. By the time he had enough of the apples to sell (many years after their invention), grocery stores were starting to evolve. Plain ol’ iceberg was giving way to different lettuces, the beginning green shoots of the Kale Revolution. The stores had changed their tune. They were open to this new variety, and more.

Honeycrisps took off. They didn’t just sell; they became the #1 selling and grossing product in the stores – toppling soda, peanut butter, chocolate chip cookie dough, you name it. They reigned supreme.

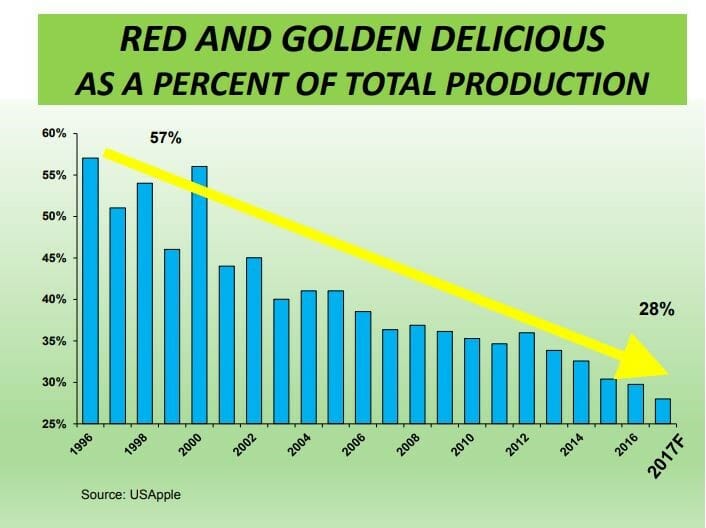

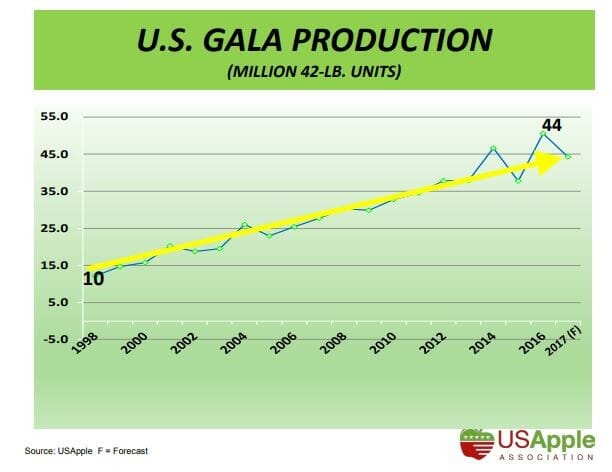

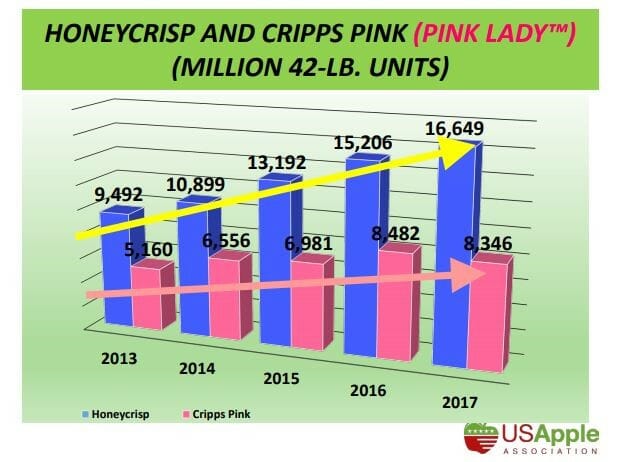

Ever since the Honeycrisp apple, Red and Golden Delicious Apples at a % of the total have cratered. Other Apple varieties like Honeycrisp, Pink Lady/Crisps, and Gala have flourished as illustrated in the following charts.

The moral of our story is that there were zero Honeycrisps in 1990. Today there are more than 16.5M bushels or 700 million lbs. And that number is still exploding higher.

That’s because, on average, Americans eat about 18.5 lbs. per person per year of apples, according to Statista. If we do the math using this figure, it would calculate to approximately 6 billion lbs. of apples per year (18.5 x 325.7 million in US population)! But if we adjust to include only the adult population, our number would be a bit lower, at around 5.5 billion lbs. That’s a lot of apples Americans are snacking on!

Of course, Honeycrisps weren’t the end of the line for apple innovation. Today, there are over 8,000 varieties of apples – more than any other fruit. Names like Fuji, Gala, McIntosh, Jazz, Rome, Cripps Pink/Pink Lady®, Empire, and Braeburn are commonly spread across the produce section of everyday grocery stores.

Bedford and Cortier revolutionized the dying apple industry into an innovative business that continues to thrive today.

If we take the top-selling kinds of apples – Gala and Red Delicious – and average the cost per pound using data from the USDA, we get $1.21. Take it one step further and multiply the price by the number of apples we consume each year (6 billion), and it comes to $7.3 billion of apple retail.

To fill the demand, the US has about 7,500 apple producers. These folks grow around 250 million bushels each year, or 10.8 billion lbs., that will either be sold fresh, or processed into juice, applesauce and other household staples. The wholesale value of the entire harvest comes in at $4 billion.

With numbers like these, it’s no wonder we’re the second largest grower of apples in the world (behind China). On average, the US exports about 25% of our collective crop, while also importing about 5% to keep our grocery store shelves stocked.

And what’s interesting is that the landscape of apple production continues to evolve. Today, there is such a thing as “branded apples,” as apple varieties that are not only patented (as Honeycrisps were) but also trademarked. Why? Because patents wear off in 20 years, but trademarks don’t. Hence, the names like Cripps Pink/Pink Lady® and The Sweet Tango ™.

To close, I always think it’s valuable to put big statistics in a more tangible perspective. Let’s talk sales of apples of one well-known retailer – Walmart.

How many apples does Walmart sell? This is a tricky number to get to, but let’s walk through it. Walmart generates about $160 billion in annual grocery sales. And, according to the New York Times, this represents a 23% share of the US grocery market. So, if we assume that apples are distributed evenly across all grocers, that means Walmart sells between $1.5 billion and $1.7 billion in apples annually. This translates into around 1.3 billion to 1.4 billion pounds of apples every year. And that’s just one grocer!

Apples are a critical part both of our food economy and our overall American economy. And the success story behind how the industry rebounded in just two decades is an incredible tale. To bring apple growers from surviving to thriving, it took hard work, patience, innovation, and faith. At its core, the story of the Apple Revolution is a story of the payoff of the American dream.

How do you like them apples?