Who can argue that innovation is a bad thing? American ingenuity sets us apart from our global competitors. In recent years, however, innovation has been failing our economy.

The US is a haven for technology – robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), you name it. Yet despite all this bigger and better tech, productivity in the US has been somewhat dismal since the Great Recession.

And productivity, which measures how efficiently labor and capital are being used in an economy to produce a given level of output, is critical to our Gross National Product (GNP).

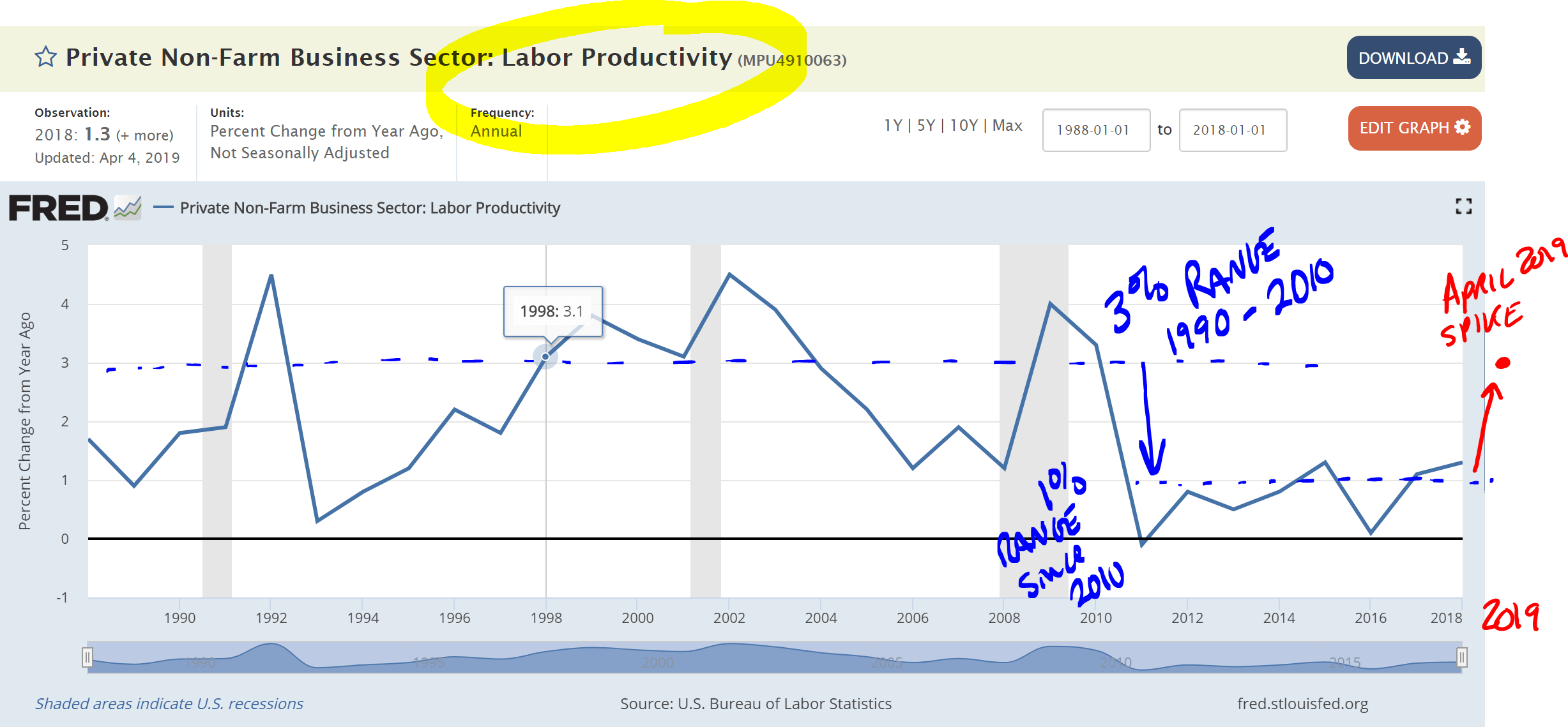

This dip in productivity has been difficult for economists to explain. Looking back to 1990 and through 2009, productivity growth was regularly in the 3% range. This is well and good because productivity growth also happens to be a significant part of a growing Gross Domestic Product (GDP). That’s because companies earn money, and then invest in everything from software to computers to robots to factories. So, you can see how real productivity is a driver of overall economic growth.

We have seen massive innovation in the past decade. Think about iPhones, Tesla, and 3D printing. Consider the flurry of new, innovative services, such as Uber, Airbnb and those crazy motorized scooters you see on every street corner.

The problem is that these innovations aren’t improving productivity. Until this most recent quarter, where we saw 3.2% productivity growth, we’ve been limping along at a measly 1% for a decade. (I believe that recent bump is the result of tax incentives and capital expenditures finally ramping up.) Those numbers are way off from what we experienced in the 90s to the 00s.

Real productivity changes the way we work, how efficient we are and how well we work. The steam engine, electric power, telephone, internal combustion engine, and airplane are all enshrined in the Productivity Hall of Fame.

The desktop computer and office software are a modern addition to that pantheon. These powerful tools allowed companies to do more with fewer secretarial and administrative employees and placed incredible computing power once available only to the largest companies in the hands of small businesses and visionary entrepreneurs.

But how about those motorized scooters that litter the streets? This is an example of what was an innovation. Whether it still is now that there are a handful of companies offering a slew of different colors of the exact product is debatable. What is fact, however, is that these scooters did nothing to increase productivity. Sure, you might hop on one after a trip on Marta to reduce your commute time, but that doesn’t make you any more productive.

And while services like Uber and Airbnb are indeed innovative, they aren’t making much of an impact on productivity. Uber is simply a clever and sometimes preferable alternative to taxis and driving your own car.

Another example: Those ketchup containers with a foil top that allows you to either rip off a corner and squirt the ketchup, or tear off the top and dip your fries straight in. That’s innovation; that’s new consumer choice. But in no way whatsoever does this innovation make you, me or even fast-food chains more productive.

I’ve been perplexed and troubled by the lack of productivity expansion in the US over the past decade. But with the increase in this past quarter’s productivity growth, I do remain optimistic.

It seems to me that the tax stimulus is working and that after a decade of lethargy, companies are getting back to the basics – how to turn innovation into productivity, thereby ramping up the economy. And isn’t that what we’d all like, ketchup aside?